(Originally published in The Journal of Education, 1981. This booklet has been missing for about 20 years and we just located at our headquarters and are so glad we can share it with you. And we share it with you now in honor of the anniversary of Dr. Gordon’s passing on August 26, 2002.)

Discipline Defined

When parents and teachers talk about disciplining children they get entangled in a jungle of muddled meanings, as do most professionals who deal with discipline in their books for parents or teachers, as I shall later illustrate. Probably the most common confusion is the failure to differentiate between two radically different kinds of discipline: self-discipline and externally imposed discipline. Everyone values self-disciplined children. No argument there. With the self-disciplined child the responsibility for, and the control of, his or her behavior resides within the child.

With the second kind of discipline – that exercised by parents and teachers over children – the responsibility for, and the control of, the child’s behavior resides within the adult. This fundamental difference is one of inner control versus external control. Suffice to say, my argument is that externally imposed discipline cripples children; certainly self-discipline does not.

I must also be precise about the difference between the noun “discipline” and the verb “to discipline.” Again, everyone values having “discipline in the classroom” (the noun), which implies order, rules, regulations, consideration for the rights of others, government – all necessary elements to make both teaching and learning possible. However, the verb, as in “disciplining the students,” usually means the teacher employs some sort of external control. Under the verb “to discipline,” I find in my Synonym Finder such synonyms as:

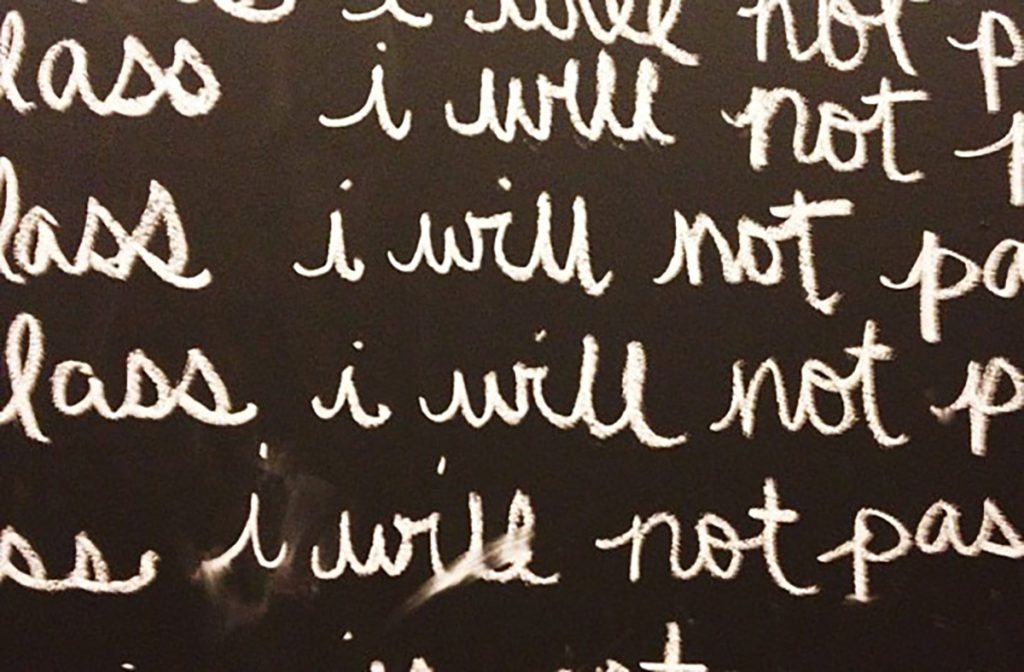

control, ride herd on, direct, govern, supervise, manage, hold in hand, keep in line, regulate, regiment, restrain, check, curb, hold or keep back, contain, arrest, harness, bridle, rein in, hold in, leash, muzzle, restrict, restrain, confine, chastise, reprimand, reprove, rebuke, make an example of, punish, castigate, penalize.

I need not point out that what cripples children is the verb “to discipline,” as well as all the other verbs that describe what parents and teachers actually do when they try to discipline children.

Of course, there are other applications of discipline besides those for children. Military officers discipline subordinates for the purpose of instilling obedience to authority; circus trainers discipline animals to coerce them into performing unnatural and spectacular tricks; owners send their pet dogs to discipline school where they are trained to perform certain behaviors upon command. Whether with animals or children, discipline is a deliberate attempt to exert some sort of strong control over another. It is important to understand where the controllers get their ability to control.

In the case of disciplining children, the controller’s aim is to place himself or herself in charge of the child, in a position to dominate or have mastery over the child. The controller’s hope, of course, is that the child will be compliant, submissive, tractable, non-resisting, or yielding – above all, obedient.

The first source of a controller’s power is possession of the “means’, for satisfying the controllee’s needs. If my small child is very hungry, with my exclusive access to the food I can use this power to make him set the table for me, saying, “Jimmy, as soon as you set the table for me, you can start eating your dinner.” Or if my daughter wants desperately to get e new dress, I can promise, “lf you clean up your room every day this week, I’ll give you the money for your new dress.” Call this controlling by having “rewards” that satisfy some need of the child.

Another source of power is possessing the means to inflict pain, unhappiness or discomfort on children. Wanting my son to eat his vegetables, I might threaten him with, “Until you eat your vegetables, you stay at the table and no TV show.” Call this controlling by having the means to “punish.” Rewards and punishments are the ultimate source of the power of controllers to control.

With very young children, adults have in their possession a most impressive storehouse of things kids need: food, drink, clothes, toys, money, candy, gum, all sorts of favors (singing or reading to them, playing with them, pushing them in their wagons, piggybacking them), coloring books, hugging and kissing, and scores more. Similarly, with infants and toddlers, adults possess a mighty arsenal of punishers. In addition to the capability of depriving children of any one of the above rewards, adults can inflict physical pain, restrain, restrict, confine them to their rooms, yell and scold, push them away, force unwanted food down their throats, instill fears in them (“You won’t go to heaven,” “God will punish you,” “You’ll drive me to an early grave”), ignore them, give them the silent treatment, and hundreds more you can add from your own childhood years.

Now we’re ready to explain exactly how rewards and punishments work to get the job done for controllers.

How Rewards Work

Two conditions must always be met for rewards to work effectively or work at all:

- The child must want or need something strongly enough to submit to the controller’s control (to produce the behavior the controller wants).

- The reward offered by the controller must be seen by the child as satisfying some unmet need.

With these conditions met, controllers have a choice of using rewards to control children in one of two ways: they may promise the reward contingent on the child first submitting to the control or they may wait until they observe the child engage in the desired behavior and then “administer” the reward as an unexpected consequence. An example of controlling by promising a reward: you want your child to go to bed, so you say, “If you go to bed right now without a fuss, I’ll read you a story.” An example of controlling by rewarding after observing a desired behavior; a teacher wants a child to stop getting out of his seat, so each time he observes the child in his seat he smiles and says, “You’re being a good little boy staying in your seat.”

Exercising control over children by using rewards goes by a variety of names, some of which you’ve undoubtedly heard: behavior modification, behavior training, operant conditioning, positive reinforcement, behavior engineering, behavior shaping, behavior management. Whatever name is used, the basic method of control by rewards is changing behavior by arranging the consequences of the change so that they are felt as positive or rewarding to the child. The principle is well known and quite valid: BEHAVIOR THAT IS REWARDED TENDS TO BE REPEATED.

How Punishment Works

As with rewards, certain basic conditions are required to make punishment work effectively in controlling behavior.

- The punishment must be felt by the controllee as depriving, noxious, denying, unwanted, injurious – i.e., it must be aversive to the controllee (antagonistic to his or her needs).

- The punishment must be strongly enough aversive to bring about elimination of unwanted behavior.

Punishment can work one of two ways. First, the adult can threaten or promise to use punishment if the child does not change his or her behavior, e.g., “If you don’t stop that this instant, I’ll give you a thrashing you’ll never forget.” second, the adult can actually administer the punishment as e consequence of some behavior unacceptable to the adult, e.g., “You disobeyed me and rode to the park; now you can’t ride your bike for a week.”

Exercising control by the use or threat of punishing consequences goes by a number of names: behavior modification, aversive conditioning, avoidance training, behavior management, or disciplining.

The basic principle upon which control by punishment works is this: BEHAVIOR THAT IS PUNISHED TENDS TO BE DISCONTINUED.

The Conditions for Having Power

Controlling with rewards and punishment requires that the controller be in possession of the appropriate means to meet the needs of the child as well as the means to frustrate or deprive those needs. It’s a simple matter of needs fulfillment and needs deprivation, externally engineered or managed, with the controller holding title to the means and taking full charge of arranging when they are doled our or dispersed. Thus, the controller has mastery in the relationship, he clearly has the upper hand. Even more important to recognize, the controller always chooses the behaviors judged acceptable, those to be reinforced by rewards, as well as the behaviors judged unacceptable, those to be punished.

For this kind of control to work, the child must be kept in a continuous state of dependency and fear – dependent on the controller for the rewards he or she possesses and fearful of their punishments. In fact, one could say that the child must be kept locked in the relationship, needing what only the controller has to give and being unable to escape from the punishment the child fears.

For example, a mother employing candy to reinforce a child’s doing his chores or homework would lose her power to control if the child had access to all the candy he wanted. Obviously, as children get older and acquire the ability to earn their own candy money, this is exactly what happens.

Similarly, a father employing physical punishment to decrease or eliminate swearing will lose his power as soon as the youngster gets too big to spank. This too happens in all families. As children get older and bigger, and as they increasingly find ways to meet their needs independent of parents, parents lose their power – they run out of rewards or punishments that work.

This is the explanation for the almost universal experience of parents who use a lot of control when their children are young, when they approach adolescence, their parents are puzzled and dismayed to discover they are losing most of their control. Usually parents say something like, “Jan used to be a good child but now that she’s older we have almost no influence over her.” What they mean is that they have no more control – they never did learn how to use influence.

The Problem with Using Rewards

Controlling the behavior of children by using rewards is not as simple as it seems on the surface. The principle is sound, and it has been validated by many hundreds of “experiments” in which psychologists have successfully modified the behavior of children by focusing only on rewarding (“reinforcing”) the particular behavior the controllers selected as “desirable.” This method has been particularly successful with children who are retarded, autistic, emotionally disturbed, or hyperactive, where the goal is to get such children to engage in behaviors that are more socially appropriate or behaviors that will make the children easier for their caretakers to manage.

While these experiments validate the basic principle of reinforcement through rewards, anyone who takes the time to read the reports of these experimenters can’t help but see that they involved very complex procedures including laboratory-like conditions, meticulous recordkeeping, and consistent and precise timing in scheduling the application of the rewards. And, more often than not, bringing about permanent behavioral change takes a lot of time, often many weeks or months of working with the child. Truly, behavior modification is a science that requires amazing expertise and a lot of patience.

Unfortunately, few parents or teachers have either the expertise or the patience required to employ this high- technology method. Considering its complexity, it is a method that I feel is neither appropriate nor practical for parents or teachers in dealing with the problems they encounter daily in their relationships with children. In fact, when parents and teachers try to control children solely with rewards, they inevitably run into some difficult problems: the child may not ever come up with the desired behavior which the parent is ready to reward; their rewards lose their value; they run out of rewards; children get rewarded by their peers for behavior that is unacceptable to parents or teachers; children grow older and they’re much less dependent on parents and teachers for satisfying their needs; some children find it too difficult to earn the rewards offered them (high grades in school); or acceptable behaviors often go unrewarded when parents or teachers are busy. Other problems can be added to this list, but suffice it to say, most parents and teachers find that reinforcing acceptable behaviors with rewards doesn’t work very well. What happens then is that they begin using punishments to eliminate unacceptable behaviors.

Now parents and teachers run into another set of problems. Like rewards, punishments have to have strength to modify a child’s behavior. Parents usually start out using mild punishment (a reprimand, a scolding, an angry look), but, as the behavior engineers have proven, mild punishments seldom work. The most common scenario to occur next is that the adult begins to employ more severe punishments – some form of deprivation (not taking the child to the baseball game) or some form of physical punishment – such as slapping, hitting, swatting, pinching, kicking, paddling, switching or belting. Sometimes these punishments work; more often they do not, resulting in the unacceptable behavior being repeated immediately or later, which provokes more punishment.

Although greatly oversimplified and sketchy, my description of what happens when parents and teachers try to use power (rewards or punishments) to control children squares with what I have learned from working with families and schools. I cannot escape the conclusion that we are a nation in which most parents and teachers rely heavily on using rewards and punishment to control children. Finding that rewards don’t work very well, American parents punish their children, usually with some form of physical violence.

The Frequency of the Use of Physical Punishment

Just how pervasive is physical punishment? Four different surveys, conducted in the United States and in Great Britain, have been reported in the literature, (Blumberg, 1964; Bronfenbrenner, 1958; Erlanger, 1974; Stark & McEvoy, 1970). AII studies reported very high percentages of parents who said they had used physical punishment at some time in their child’s life. The percentages ranged from 84% to 97%.

Contrary to popular belief, it is not just very young children who are assaulted by their parents. A recent survey of a large sample of American parents [Straus, Gelles & Steinmetz, 1980) reported the percentages of children of various ages who were victims of some form of physical violence from their parents:

- 3-4 year olds 86% of children

- 5-9 year olds 82% of children

- 10-14 year olds 54% of children

- 15-17 year olds 30% of children

In this same survey, 61% of parents reported using physical punishment at least once a week! These startling statistics refute the commonly held belief that American parents are too lenient, too permissive, and too child-centered.

Tragically, much of the physical punishment is far more severe than a swat on a child’s behind. From their nationwide survey of over 2,000 families, Straus et al. estimate that between 3.1 and 4.0 million children have been kicked, bitten or punched by a parent some time in their lives. Between 1.4 and 2.3 million have been beaten up. These authors, themselves surprised by their findings, conclude: “For a child to be kicked, beaten, punched or beaten up once every other month came as a surprise…. Child abuse may be a chronic condition for many children, not a once in a lifetime experience for a rare few” (p. 63).

As for the frequency of physical punishment in the schools, consider first that only four out of our 50 states have enacted laws completely prohibiting corporal punishment in the schools: New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maine, and Hawaii. An article in the November, 1972 issue of the journal Nation ‘s Schools (1972) reported that the Dallas public schools reported an average of 2000 incidents per month of using corporal punishment. Almost double that number was reported by the Houston School District. And various polls show that from 60% to 80% of parents support the legal use of corporal punishment on their own kids by the schools (Reardon & Reynolds, 1979).

The Crippling Effects of Physical Punishment

Parents who use physical punishment are woefully uninformed about the effects of their violence on children: it can be damaging to their physical health, their emotional health, and their social competence. I have little hope of improving the quality of family life or of decreasing the incidence of poor mental health in our country until parents have a better understanding of the damaging effects of punishment.

Obviously, physical punishment carries the risk of inflicting serious injuries on children. Almost four out of one hundred children risk serious injury each year from parents using at least one of the following forms of punishment: kicks, bites, punches, burns, beatings, use of guns or knives (Straus, Gelles & Steinmetz, 1980). The frequency of child abuse, which until recently remained a national secret, has become a national tragedy.

Not as obvious are the damaging effects of physical punishment on the emotional and psychological health of children. A study by psychologist Robert sears (1961) revealed that l2-year-old boys whose parents rated high on restrictiveness and harsh punishment showed strong tendencies toward self-punishment, accident proneness, and suicide intentions. A study by psychologist Stanley Coopersmith, author of Antecedents of Self-Esteem (1967), found that children with low self-esteem, as compared with children of high self-esteem, had mothers who used more arbitrary punitive discipline and less reasoning.

In a study of 230 graduate students, psychologist Goodwin Watson (1934) found that students who had rated their parents in the top quartile as to punitiveness and strictness revealed the following in extensive self-reports of their emotional health:

- More hatred and restraint toward their parents

- More rejection of their teachers

- Poorer relations with their classmates

- More quarrels with friends

- More shyness

- More unsatisfactory love affairs

- More worry and anxiety

- More guilt

- More unhappiness and crying

- More dependence on parents

One of the most frequently investigated effects of punishment on children is aggression. In summarizing his extensive review of these studies, Barclay Martin (1975), in the Review of Child Development Research concludes:

Overall this body of research provides impressive evidence that harshness of parental punishment is likely to be associated with child aggression … These results support the theoretical contention that punitive discipline serves both as a frustrating instigation to aggression and as an aggressive model. (p. 510)

In other words, in direct contrast to the conventional and “common sense” belief of parents that punishment must be used to prevent aggressive behavior of children, the evidence clearly indicates the opposite – namely, harsh punishment actually promotes aggression in children.

Physical punishment literally trains youngsters to be aggressive and to use violence themselves. Thus each generation learns to be violent from the previous generation. Consider these frightening findings from the previously cited survey by Straus et al. (1980):

Nearly 100% of children whose parents used a lot of physical punishment had severely assaulted a brother or sister, as compared to only 20% of children whose parents did not use physical punishment.

Husbands who had experienced severe violence at home as children have a 600% greater rate of wife-beating than husbands who came from non-violent homes.

One of the most common justifications for using punishment is parents’ fear that without it their children will not learn obedience to authority and respect for the law and will become juvenile delinquents or criminals. Unfortunately, the facts do not support the belief that punishment will promote respect for authority. Studies of the family backgrounds of both male and female juvenile delinquents consistently have found a pattern of harsh, power-assertive punishment by their parents (Martin, 1975). A study of violent inmates in San Quentin prison found that 100% of them had experienced extreme violence in their homes between the ages of one and ten (Maurer, 1976). A study conducted in

Oregon showed a positive correlation between school vandalism and corporal punishment. Schools using more physical punishment had more vandalism; those using less physical punishment had less vandalism (Hyman, McDowell, & Raines, (1975).

In addition to the findings from these experimental studies, clinical evidence is reported in the journals linking coercive punishment to adolescent drug abuse, psychosomatic illnesses, running away from home, truancy, adolescent depression and suicides, and teenage premarital pregnancies.

There is one other crippling effect of punitive discipline, which may be the most pernicious of all because of its effect not only on the health of individuals but also on the health of our society. For reasons not clear, some children learn to cope with punitive discipline with submission, subservience, compliance, deference and obedience. Because these behaviors are considered virtues by so many people in our society, they tend to get rewarded and hence reinforced. Authors of books for parents are reaching millions of mothers and fathers with messages which I consider quite dangerous: “Make your children obey,” “Use your authority to control your children.” Here are the titles of such books, all recently published:

- Dare to Discipline

- Power to the Parent

- The Strong-Willed Child

- Parents on the Run: The Need for Discipline

- Parent Power

- Assertive Discipline

Some of the authors of these books cite passages from the Bible, such as: “Spare the rod, spoil the child,” and “Children obey your parents in all things, for this is well pleasing unto the Lord.” James Dobson, whose book Dare to Discipline has sold over a million copies and is used in study groups in hundreds of Protestant churches, tells parents that physical punishment to get obedience is the Christian way to parent. In his newest book, The Strong-Willed Child (1978), he tells parents:

Should a spanking hurt! Yes, or else it will have no influence. . . . Two or three stinging strokes on the legs or bottom with a switch are usually sufficient to emphasize the point, “You must obey me.” (p. 47)

By learning to yield to the loving authority of his parents, a child learns to submit to other forms of authority which will confront him later in life – teachers, school principals, police, neighbors, and employers.

Bill Gothard, a fundamentalist minister whose lectures attract as many as a thousand participants in cities where he appears, preaches that Christian families must function as a hierarchy of obedience to authority – God on top, father next, mother below him, and finally the children occupying the lowest level.

Logan Wright, a psychologist whose book Parent Power (1978) earned him the Distinguished Contribution Citation in the 1977 Media Award from the American Psychological Association, tells parents on his first page:

The most important reason for seizing control is that you must be able to control a child before you can really support and love him. (p. 17)

The advocates for greeter control of children are many; those who extol the virtues of obedience to authority have a loud voice. Have they already forgotten the Nazi extermination of European Jews carried out by German soldiers in the name of obedience to the authority of their superiors, and the horrible actions of American soldiers against Vietnamese citizens, and Reverend Jim Jones’ use of “duty to obey orders” to convince his cult members to destroy first their own children and finally themselves?

The lesson that these crimes against humanity should teach us is that punitive discipline to bring about blind obedience to authority conditions people to view themselves solely as instruments for carrying out another person’s wishes, not as individuals responsible for their own actions.

Nowhere has this lesson been more dramatically demonstrated than in the pioneering experiments of Stanley Milgram and his associates (1974), for which Milgram was awarded the annual sociopsychological prize of the American Association for the Advancement in science. By using an ingenious laboratory procedure in which his subjects were pressured by an “authority” to administer what the subjects thought were strong and painful electric shocks to another person, Milgram identified those who were obedient to authority and those who were not. Two-thirds of his subjects could not bring themselves to disobey the authority figure even though many were convinced of the wrongness of what they were doing (physically harming another person).

The most common adjustment of thought in these obedient subjects, Milgram concludes, is to see themselves as not responsible for their own actions. Each sees himself not as a person acting in a morally accountable way but rather as the agent of external authority – the age old story of “just doing one’s duty.” Milgram stresses the point: “The disappearance of a sense of responsibility is the most far-reaching consequence of submission to authority” (p. 8).

The conventional wisdom in this country, as well as one of the tenets of Freudian theory, holds that if children first are disciplined to obey authority, later they will internalize the once external authority and become self-disciplined and self-controlled. Now we have ample evidence that the opposite occurs: obedience to authority brings about the disappearance of self-control and self-responsibility.

Milgram called my attention to Harold Laski’s article, entitled The Dangers of Obedience, in which he writes:

…civilization means, above all, an unwillingness to inflict unnecessary pain. Within the ambit of that definition, those of us who heedlessly accept the commands of authority cannot yet claim to be civilized men. Our business, if we de sire to live a life not utterly devoid of meaning and significance, is to accept nothing which contradicts our basic experience merely because it comes to us from tradition or convention or authority.

The brilliant historian C.P. Snow (1961) has given us these words: “When you think of the long and gloomy history of man, you will find more hideous crimes have been committed in the name of obedience than have ever been committed in the name of rebellion” (p. 24).

We can now add to our list another crippling effect of coercive control of children – namely, the loss of self-control and self-responsibility through submission to external authority.

Teaching Parents and Teaches Alternatives to Discipline

For over two decades I have been fully committed to an educational program in which both parents and teachers are given formal training in courses designed to teach effective alternatives to power-based, authoritarian control of children. These courses, called Parent Effectiveness Training (Gordon, 1975) and Teacher Effectiveness Training (Gordon, 1977), have a common objective: to help the participants learn the interpersonal skills that will enable them to establish relationships with children that are egalitarian, collaborative, synergistic, collegial, reciprocal, mutually beneficial, and democratic. In these courses, parents and teachers are shown a new model, a new paradigm, a new theory of adult-child relationships. This Effectiveness Training model replaces control with influence; it replaces domination with leadership; it replaces win-lose methods of conflict-resolution with a win-win (or no-lose) method.

In this model of democratic relationships there is no place for the “language of power,” which includes, among others, such concepts as:

Authority Discipline

Power Obedience

Control Restricting

Setting limits Ordering

Being strict Compliance

Punishment Respect for authority

Demands Boss

Commands Coercion

Most parents and teachers are the victims of either-or thinking – either the adult must retain power or the child will assume it. They see but two choices: adult authority or dangerous permissiveness. The challenge of both of our courses has been to show parents and teachers that they have another choice, an alternative to either authoritarianism or permissiveness.

I will describe in more detail the content of these courses, but for the sake of simplicity I will refer only to the Parent Effectiveness course, trusting that the reader will be able to make the transfer easily from that course to Teacher Effectiveness.

We first help parents understand how they are locked into win-lose methods. When parents use punitive power to resolve the inevitable conflicts in parent-child relationships, the parent wins and the child loses. Being permissive, on the other hand, means the parent loses and the child wins. In both approaches one person in the relationship experiences needs satisfaction, the other needs deprivation. In both approaches the relationship suffers because there is a loser – someone who feels deprived, frustrated, disappointed, resentful, angry, retaliatory, and/or rebellious.

Parent Effectiveness offers parents an alternative method of resolving parent-child conflicts: the No-lose Method. This involves parent and child joining together in a problem-solving process to define their conflict and search for a solution that will be acceptable to both, a solution that will result in mutual need-satisfaction, a solution that leaves no one the loser (or leaves both the winner) .

Actually, most parents already are familiar with the No-lose (or Win-win) Method, having had experience using it in solving some of their conflicts with friends, spouses, or people with whom they work. However, only a very small percentage of parents have thought of employing it with their children. So, to get them to use it in that relationship requires not only prior practice via a lot of role-playing in the classroom, but also requires helping them to understand that the method is not giving in to the child, not sacrificing their own needs – i.e., that parents will have their needs met, but so will the child, an added benefit to be sure.

Thus, the core of the P.E.T. course is teaching parents how to live democratically with their children by employing a process that involves the participation of both parents and children in setting all rules, dividing up the household chores, and finding mutually acceptable solutions to the hundreds of conflicts (minor or major) that occur in all families over such issues as bed-time, TV, noise, cleanliness, use of the car, picking up toys and clothes, use of the phone, children’s allowances, health habits, safety practices, and the like.

For the No-lose Method to work, however, the parent-child relationship must be one in which there is an ongoing and continuous respect for the feelings of each other and a mutual concern for the well-being of the other. Consequently parents must be taught how to listen and show empathy and understanding when children share their feelings and problems.

P.E.T. teaches parents the skills of the professional counselor – a special kind of listening that makes children want to talk to them. In addition, P.E.T. teaches parents how to be more open, honest and direct in sharing their own feelings and problems so that their children are more apt to listen to them.

Thus, Parent Effectiveness, in addition to giving training in democratic problem-solving and conflict-resolution, teaches effective interpersonal communications skills. Parents are taught and coached in empathic, nonjudgmental listening, with instructors using some of the same pedagogical techniques developed by Carl Rogers and his associates back in the late 40’s and early 50’s at the University of Chicago where we were training graduate students to be effective helping agents, counselors and therapists. Our aim in Parent Effectiveness is to teach parents how to provide a new and different kind of help when their children encounter problems in their own lives. With this new counseling approach, parents move away from their usual helping posture of taking control-giving advice, preaching, teaching, moralizing, warning, directing, and giving solutions. They move toward â new role that fosters a climate in which children assume ownership of their problems, take on the responsibility to begin their own problem-solving, and search for their own solutions. The idea, in fact the faith, that people have untapped capacities to solve their own problems, given a relationship with a warm, empathic, accepting and understanding listener, is, in my opinion Dr. Carl Rogers’ greatest contribution to the world and the clearest indication of his creative genius.

Parent Effectiveness is also a kind of assertiveness training, in that we teach parents to acquire a greater respect for their own human needs, for their right to have their own needs met. We help them understand that a healthy relationship cannot be a one-way relationship; parents must learn how to get their needs met, too. Parents learn how to convey assertively to the child, “I have needs,” “I have a problem right now,” or “I need you to listen and try to understand me.”

Parent Effectiveness strives to change the speaking habits of parents. From the almost universal habit of sending blameful “You-messages” (you are a bad boy, you are thoughtless, you have ruined my day, you are driving me crazy, you stop this instant, you are driving me to an early grave), parents are taught a new habit of sending l-messages (l need, I want, I have a problem, I’m bothered, I am worried, I would appreciate, I am tired, I need help, I am scared). In other words, Parent Effectiveness shows parents how to be more open, honest, and direct rather than manipulative; how to be self-revealing rather than blaming; how to be assertive rather than demanding or commanding; how to be self-disclosing rather than accusatory or punitive. Using this new “I-language,” parents more often and more successfully influence kids to modify their unacceptable behaviors, but out of consideration for their parents’ needs, not from obedience to their authority.

We have learned that the parent-child relationship differs from most other relationships in a very significant way. Most parents feel they “own” their children. From this it follows that they feel they have the right, in fact the duty, to impose on their children the values, beliefs, and standards most dear to the parents. The method most parents use to try to bring about such values, indoctrination, goes far beyond teaching by example or by instruction. Most parents rely heavily on punishment or threats of punishment. Few parents realize that it is in the values arena that their power is not only most ineffective but also most destructive to the parent-child relationship. For, as children move into adolescence, they develop strong needs for independence and autonomy in choosing their own values and beliefs. Consequently, youngsters strongly resist parents’ attempts to impose their values and beliefs or deny children their freedom to choose their own. In fact, some youngsters respond to coercive power by consciously adopting the very opposite values of their parents. Such “rebellion” usually brings about complete alienation of parent and child, an almost irreversible deterioration of their relationship, and the resulting loss of any influence of the parent on the child. Unfortunately, few parents understand the paradox that by using power, parents actually lose influence.

Our aim in Parent Effectiveness is to show parents the critical difference between coercive control and influence. Control depends on the use of power; influence depends on the use of persuasion and education. Emphasizing that they have the legitimate responsibility to try to influence their children’s values and beliefs, we show parents what they must do to be effective influencers. Here we draw principally upon the body of knowledge about what it takes to be an effective consultant: (1) modelling the behaviors the influencer values, (2) verbally sharing those values and beliefs openly and honestly, (3) leaving complete responsibility with the client for accepting or rejecting the values and beliefs of the consultant, (4) refraining from hassling, cajoling, or putting down the client.

Limiting their role to that of a consultant to their kids, even if an effective one, is not an easy adjustment for parents. However, most parents have previously experienced hassles and battles over values, especially with preteens and adolescents and therefore, they usually understand that their power methods have not been effective. Furthermore, we find that most parents are somewhat relieved at the prospect of leaving responsibility with their youngsters rather than assuming the responsibility themselves for their children’s values and beliefs.

Conclusion

In view of the growing body of evidence that power-based discipline is crippling to children and youth, parents and teachers should be made aware of the risks they take when they use punitive and coercive discipline. It is unlikely, however, that parents and teachers will change much without acquiring, through formal training, the skills to use non-power alternatives. Parent Effectiveness Training and Teacher Effectiveness Training do provide an alternative new model for dealing with children at home and in the schools – a model for establishing non-power, democratic, egalitarian, mutually satisfying relationships. With this model of dealing with children, parents and teachers find they no longer need to “discipline” – in fact, the concept itself becomes completely foreign, incompatible with their new philosophy of relationships that are truly health giving.

©Copyright, Gordon Training International – 1981, 2017

References

Blumberg, M. When parents butt out. Twentieth Century, 173 (winterl, 39-44.

Bronfenbrenner, V. Socialization and social class through time and space. In E. E.

Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, &, E. L. Hartley, (Eds.) Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Holt, 1958.

Coopersmith, S. The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: Freeman, 1967.

Dobson, J. The strong-willed child. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House, 1978.

Erlanger, H. B. The empirical status of the subculture of violence thesis. Social Problems, 1974, 22 (December), 280- 291.

Gordon, T. Parent effectiveness training. New York: New American Library, 1975.

Gordon, T. Teacher effectiveness training. New York: David McKay, 1977.

Hyman, I., McDowell, E., & Raines, B. Corporal punishment and alternatives in schools. Inequality in Education, 1975, 23, 5-20.

Laski, H. J. The dangers of obedience. Harper’s Monthly Magazine, 1919, 159, l-10.

Martin, B. Parent child relationships. In F. Horowitz (Ed.), Review of Child Development Research, 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Maurer, A. Physical punishment of children. Paper presented at the California State Psychological Convention, Anaheim, 1976.

Milgram, S. Obedience to authority. New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Reardon, F., & Reynolds, R. A survey of attitudes toward corporal punishment in Pennsylvania schools. In I. Hyman & J. Wise (Eds.), Corporal punishment in American education. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979.

Sears, R. The relation of early socialization experiences to aggression in middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 1961, 63, 466-492.

Snow, C. P. Either-or. Progressive, February, 1961, 24.

Stark, R. & McEvoy, J. Middle class violence. Psychology Today, 1970, 4, 52-65.

Straus, M., Celles, R., & Steinmetz, S. Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New York: Anchor Books, 1980.

Watson, G. A comparison of the effects of lax versus strict home training. Journal of Social Psychology, 1934, 5, 102- 105.

Wright, L. Parent power. New York: William Morrow, 1980.

This article was reprinted with permission from the Boston University Journal of Education, Volume 163, Number 3, Summer 1981.

For further information about P.E.T. write to:

Gordon Training International

531 Stevens Avenue West

Solana Beach, CA 92075.2093 USA

800.628.1197/858.481.8121