For people of a certain age in America (and that age, for many of us, is rapidly approaching “Everything I have two of, one hurts”) Fred Rogers was a daily, comforting presence on our television sets throughout our entire childhood. This month, a mostly grateful nation celebrates the fifty-year anniversary of the premiere of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, back before PBS was even a network—when the stations that would become PBS were simply a minuscule sprinkling public television stations across the continent.

Mr. Rogers changed television because he hated the medium immediately upon encountering it himself. Why? Because, as he later recalled in an interview, the first thing he saw on the new medium was “something horrible with people throwing pies at one another”—not entirely surprising, considering the sheer number of Borscht Belt slapstick comedians who populated early television. But Fred Rogers knew TV could do more. He knew it could be a transformative way to teach, comfort, develop, engage, reassure, and help children. And he dedicated the rest of his life to that mission.

He also taught us a lot about being good neighbors: about optimism, about kindness, even about success. I’ve been reflecting about Mister Rogers a lot lately, especially many of the relationships that bind Americans together seem to be unravelling, and that brings me to one of my favorite Fred Rogers nuggets of wisdom:

“There are three ways to ultimate success: The first way is to be kind. The second way is to be kind. The third way is to be kind.” —Fred Rogers

Neighbors and The Behavior Window

Let’s reflect for a moment about the people closest to us. No, not our family. Not even our friends. I’m talking about the people with whom we share visual and auditory space every day of our lives—our neighbors. Literally the people who live next door.

They’re not always necessarily people we like, in a “let’s hang out, get bottomless mimosas, have mani-pedis/go to the ballgame” kind of way. (Although if they are, what a blessing). But usually—with some notable exceptions—neighbors are people we can manage like enough to maintain cordial, nodding-and-smiling, “How-you-doing,” “I’m-fine-how-are-you,” “Nice-weather-we’re-having-aren’t-we,” “Sure-has-been-cold-out,” “Yep-well-I’d-better-get-to-work-have-a-nice-one” relationships.

The interesting thing about our relationships with neighbors is the many unspoken rules and norms for behavior and what’s acceptable and unacceptable to each other.

- Can I leave my trash cans out on the street a few hours after work on trash day?

- What about overnight?

- What about…a full day?

- Two days?

- Can I have a party and play loud music until 9:00 pm?

- OK, how about 11:00? 1:00 am?

- On a weekday?

- When will my neighbors start to get irritated? When will they get so irritated they’ll actually say something to me?

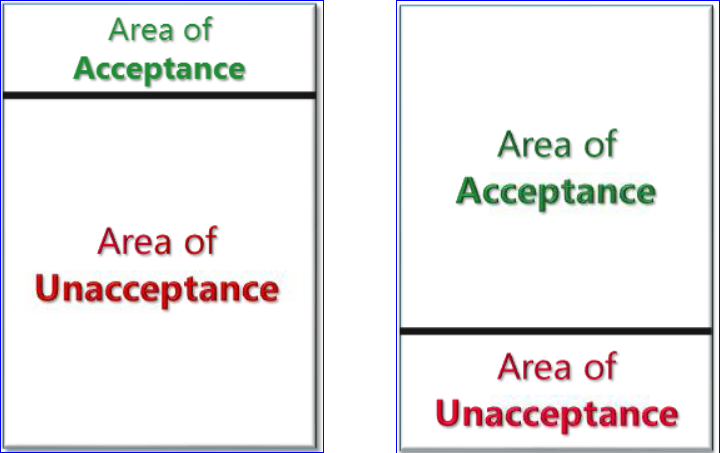

Where are our neighborly limits? Where are our behavior windows set with neighbors, versus coworkers? And once we’ve hit the area of unacceptance, where do we go from there?

It’s interesting to me that, as rational adults, in our relationships with neighbors, even without extensive formal training, most people don’t escalate immediately. One loud party does not typically change the state of our internal perception about neighbors from “Jordan and Keira next door are young and single and probably just didn’t think,” to “Jordan and Keira next door are the spawn of minor demons, clearly hellbent on making our lives miserable, and must therefore be destroyed.”

Typically, we don’t leap straight to GLOP (General Labeling of People), no matter how irritated we are with neighborly behavior that falls into our area of unacceptance. And yet, in our workplaces, a lot of us (myself included) tend to do that in the workplace. Why is that?

The Organic Neighborly Problem-Solving Conversation: Respect is the Foundation

In our neighborhoods, we give people the benefit of the doubt. And we naturally tend to have the sorts of mutually respectful, peer-to-peer, solution-seeking conversations that Leader Effectiveness Training teaches us to have (granted, in a more structured way) in the workplace. Here’s an example of a very casual, non-structured, L.E.T.-like conversation that could occur between neighbors:

“Say, Jordan, it sounded like a great party Tuesday night. So, we like 80’s music too, but we sure had a hard time getting to sleep—we have to get up really early for work—so Wednesday we were both zombies at work.”

“Oh man! I didn’t even realize how loud it was! I am sorry about that. Yeah, we really had a great time….but I can see why you’d be annoyed. We’ll keep it down next time or end it earlier for sure—and maybe you’d like to join us next time?”

“That would be awesome! Hey, do you need a hand bringing in your trash bins?”

This is what natural problem-solving between respectful adults who assume the best about each other, working out their differences, sounds like. Does it remind you of any of the skills taught in L.E.T.? It’s very much like a formal, structured L.E.T. I-Message, keeping the focus on behavior rather than the person, and the consequences for the sender.

It struck me, listening to celebrations of Mister Rogers’ life over the past week, that the foundations of L.E.T. and nearly all of Mister Rogers’s lessons come from the same deep wellspring of respect for and recognition of the fact that we are all in this together.

We all want the place we are—our neighborhoods, our workplaces, our homes—to be happy, healthy, safe, productive spaces.

And we all know, in our heart of hearts, that the way to get there is to make less noise, not more.

To be quieter, not louder.

To speak less and to listen more.

“In times of stress, the best thing we can do for each other is to listen with our ears and our hearts and to be assured that our questions are just as important as our answers.” —Fred Rogers