By: Dr. Thomas Gordon and Speed “Noel” Burch (co-author of the T.E.T. book)

Define the problem in terms of unmet needs. This is a dramatic departure from the way most people deal with conflict. People typically view potential outcomes in win/lose, zero-sum terms, it’s either this or that.

For example, suppose you and I have a conflict about the car. I need it to attend an evening class but you need the car to get to a networking event. Either I get the car or you do, right? Many, if not most people think this way, in terms of competing solutions, Either/Or, Win/Lose, Who’s the boss.

Actually, neither of us needs the car. The car is a solution. It can meet needs. I need to get to class, right? And you need to attend an event. When seen in that light, there are perhaps 15 or 20 ways those needs can be met. Some option could be that one of us hire a car service; we carpool/I drop you off first, catch a ride with a business associate going to the event; take the bus; call a taxi, etc. In some of these scenarios, the car could even be left at home.

In the 1950’s a young psychologist, Abraham Maslow, instead of studying pathology, became interested in how people become healthy and productive so he studied successful people like Ruth Benedict, Albert Schweitzer, Eleanor Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and others who seemed to live life to its fullest. He discovered that they were alike in many ways. First of all, they didn’t have to worry about personal survival or a sense of continuation. They had a number of friends and loving, supportive relationships. In addition, they had worthwhile, life affirming careers as well as frequent “peak experiences”, achievements that transcended ordinary awareness.

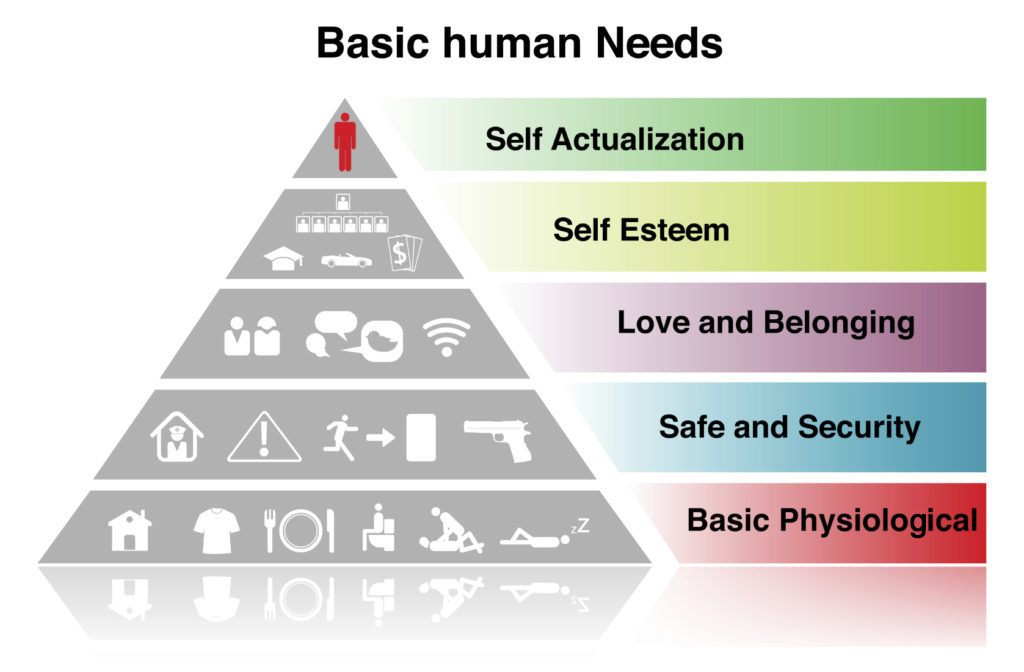

What Maslow learned from all this was that his subjects all had the same needs. Not only that, so does everyone else. He organized the needs into a hierarchy with survival (food, clothing, air, shelter, etc.) as primary, followed by the need for security, knowledge that one would continue beyond the immediacy of simple survival. He proposed that when these two lowest level needs are met, the need for relationships and belonging emerges into consciousness.

He called these social, familial needs. When people develop good relationships, can give and receive love, are able to work and play in groups a fourth set of needs emerges into awareness. These are the needs we all have to make a difference, to contribute, to define ourselves through our achievements. Finally, at the top of his pyramid is what he called self-actualization, the drive to fully develop one’s abilities, achieve ambitions, become the unique person one is, etc. Maslow was interested in people’s experiences when their needs were not met, when they were deprived. Some generalizations about his findings are listed to the right of the pyramid below. For example, the most common experience of people deprived at the lowest, survival level, is fear. When deprived at level two, security, people experience anxiety, and so on.

The reason I include this needs hierarchy is as an aid to sorting out needs from wants and solutions. For example, we don’t need apple pie … but we do need food. We don’t need Porsches but we do need transportation. Maslow’s construct can help us focus more on what’s underneath wants and solutions.

A lot of “strange” behaviors are actually attempts to meet some need. I recall a young woman, an electronic firm executive who, toward the end of one of our courses for business leaders, told about a problem she had with her husband who had suddenly become unusually quiet and withdrawn, something she resented and was puzzled about. She decided to confront this unusual behavior and picked a time when she thought nothing would interfere. She began by describing his recent actions and how upset she was about them. “I was sure Michael was either having an affair or was bent out of shape because I was now making more money than he was. I was so sure I was right that I didn’t hear him at all until he said I was like an absentee landlord, never around anymore. “Your new job may pay better but it’s keeping you occupied even when you are home,” was the way Michael put it. That was all it took. The rest of the process was easy. We both wanted more time together, so we found some. As Michael said, ‘we’ve got the same amount of time as everyone else. It’s just a matter of what we want to do with it.’ And after the affair scare what a relief it was that all he wanted was more time with me.”

Most of us aren’t bad people, just needy and in our attempts to meet our needs we may behave in odd, even self-defeating ways. Keep Maslow’s deprivation experiences in mind. They may tell you where to look for clues to a person’s unmet needs.