(from the L.E.T. book)

On becoming the leader of a group, few people seem able to resist the temptation to grab the reins, make a flying start, and plunge into the task of trying to solve all the problems alone. Understandably, the initial concern of most new leaders is to justify, as quickly as possible, their selection to those who appointed them. They want to look good, and the sooner the better. After all, what is a leader for if not to step right in and “take charge”? In the military the expression is “take command.”

Unfortunately, rushing in to take charge can get leaders into hot water. Eager to produce quick reforms, instant cures, and dramatic increases in productivity, leaders succumb to the well-known “new broom” temptation, with high expectations of sweeping clean the mess left by the group’s previous boss. Yet seldom can leaders do it on their own without the group members’ willingness and cooperation, neither of which is likely to be immediately forthcoming. Groups resist change and hang on tenaciously to their habitual ways. These “group norms” exert a strong influence on the behavior of the group members.

Unfortunately, rushing in to take charge can get leaders into hot water. Eager to produce quick reforms, instant cures, and dramatic increases in productivity, leaders succumb to the well-known “new broom” temptation, with high expectations of sweeping clean the mess left by the group’s previous boss. Yet seldom can leaders do it on their own without the group members’ willingness and cooperation, neither of which is likely to be immediately forthcoming. Groups resist change and hang on tenaciously to their habitual ways. These “group norms” exert a strong influence on the behavior of the group members.

For example, groups generally develop their own standards of what is a “fair day’s work” or a “productivity norm,” which are clearly understood by the members and informally enforced within the group. Any action of the leader that is perceived as a threat to the maintenance of this norm is strongly resisted, especially if the action of the leader is regarded as arbitrary.

Another way of looking at these resistive forces within groups is in terms of “fair exchange.” Groups strongly resist actions of a leader that might upset the group definition of an equitable cost/benefit ratio—i.e., getting fair benefits (salaries, for example) in relation to the amount of energy (cost) exerted on the job. A new leader with a new broom may be looked upon as upsetting this ratio, and the group will want to protect itself against being exploited by the organization.

Groups also strongly resist the introduction of new methods and procedures, especially if they are arbitrarily and unilaterally instituted by the leader. We all know how people get used to doing things in a certain way, so when they have to learn a new way it often seems that this requires more energy output than the group members are willing to give.

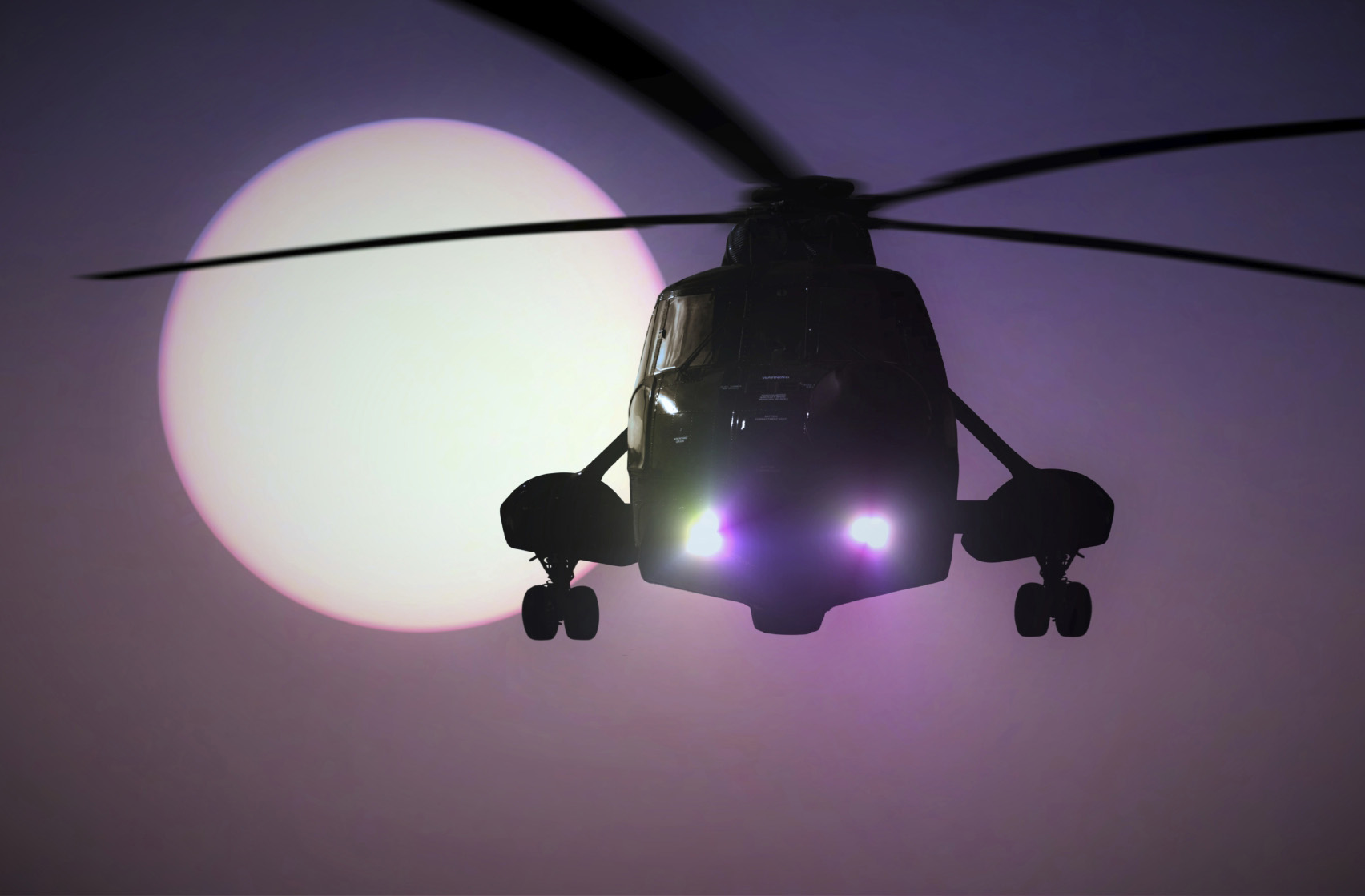

Many eager new leaders take the posture of a vigilant “overseer”—they’re going to keep very close tabs on their group members, nothing is going to escape them, and mistakes just won’t be made because they will be “on top of things.” Such “oversupervising” (or hovering over your employees like a helicopter) takes many forms, such as:

• Requiring detailed activity or progress reports

• Requiring group members to get the leader’s approval before sending out contracts, implementing plans, or making decisions

• Taking over tasks previously assigned to group members to make sure they are done “right”

• Making members “go through the leader” before initiating contacts outside the group.

One of the inevitable effects of over-supervision is resentment against the leader’s arbitrary use of power. Another effect is passive resistance to the new demands (the activity reports somehow never seem to get turned in). Even worse for the group, over-supervision makes members too dependent on the leader. They start coming to the leader with every problem. Their self-motivation drops; their initiative is stifled. They won’t grow in their jobs; the leader finds himself overloaded and overburdened, having to do everything himself. The work group now becomes a “one-man operation.” New leaders who try to over-supervise in their new job find out too late that they really are going it alone, without the benefit of all the resources of the group.