Why Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.) Works

Article by: Larissa Dann

More and more parents are educating themselves on the best way to bring up their children. We search the Internet, we read books, and we attend parenting classes. We all want to do the best by our children, to raise children that are loved and loving, confident, compassionate, considerate, and with a good sense of self-worth. In this quest for information, many parents look for evidence of effectiveness.

My experience, over 20 years of parenting using P.E.T. skills (and as a parent educator), is that the principles of Parent Effectiveness Training work. The longevity of Dr. Thomas Gordon’s book and course, and its continued uptake by parents around the world, attribute to the positive outcomes of P.E.T. on family relationships.

The question I sought to answer in this article was: Why? What is it about the P.E.T. skills that lead to favourable life results for children and parents?

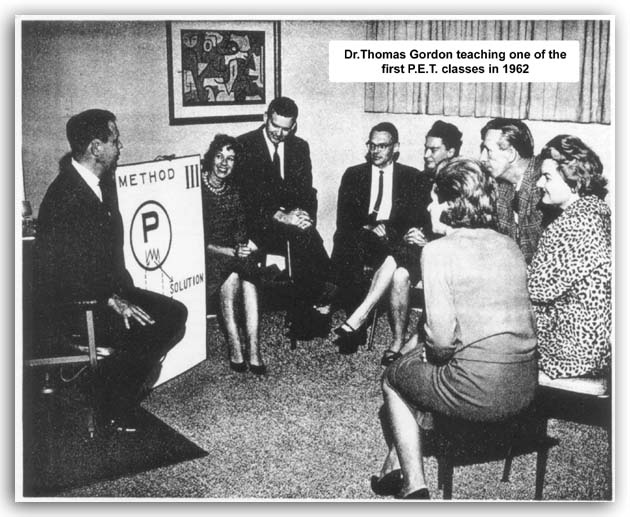

The P.E.T. course has been taught since 1962. How does current evidence support P.E.T. in terms of good parenting practice? There is a now a plethora of research that unpacks various traits and conditions necessary for good outcomes for our children. How does P.E.T. fit into this evidence landscape?

What IS Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.)?

Brief History

The parenting course, Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.), was initially devised and run by Dr. Thomas Gordon in 1962. His course was widely regarded as the first-ever course to teach parents skills to enhance their parenting experience. Dr. Gordon’s program teaches respectful communication skills to improve the relationship between parent and child. P.E.T. is taught worldwide (36 countries), with the book translated into 32 languages. An award-winning study(i) by Dr. Christine Wood (2003) examined the effectiveness of P.E.T., providing evidence of the improvement in parenting skills after parents have attended a P.E.T. class.

Skills Summary

The article Origins of the Gordon Model, neatly describes the main communication skills taught in the P.E.T. course. Hot Tips for Happy Parenting provides a précis of the skills, as does this glossary from a parenting blog, theacornwithin.com. Below is a brief summary of the main skills and ideas:

Active Listening: A method of truly hearing and trying to understand what the other person is saying (the basis of empathising). P.E.T. emphasises the inclusion of feelings in Active Listening. First conceived by the eminent psychologist Dr. Carl Rogers (for client-centred counselling), Dr. Gordon recognised that these counselling skills would also be useful for parents to improve family relationships.

I-Messages: Dr. Gordon devised the concept and structure of I-Messages. This non-blameful communication skill helps you let another person know that, in some way, your needs are not being met. I-Messages are taught in relationship courses, assertiveness courses, and management courses around the world. There are three parts to an I-Message: a non-judgemental description of the child’s behaviour; the feelings of the parent; and a concrete, tangible effect on, (or cost to) the parent.

No-lose (or win-win) Conflict Resolution: The six steps of problem solving (Method III), encourages the inclusion of all family members in a solution with which everyone can live. No-lose conflict resolution is the main skill for parents opting for an alternative to using rewards and punishment.

Avoiding the use of rewards and punishment. P.E.T. examines in detail the effects of using rewards and punishments on children. The skills taught within the course offer an alternative to the external discipline of rewards and punishment.

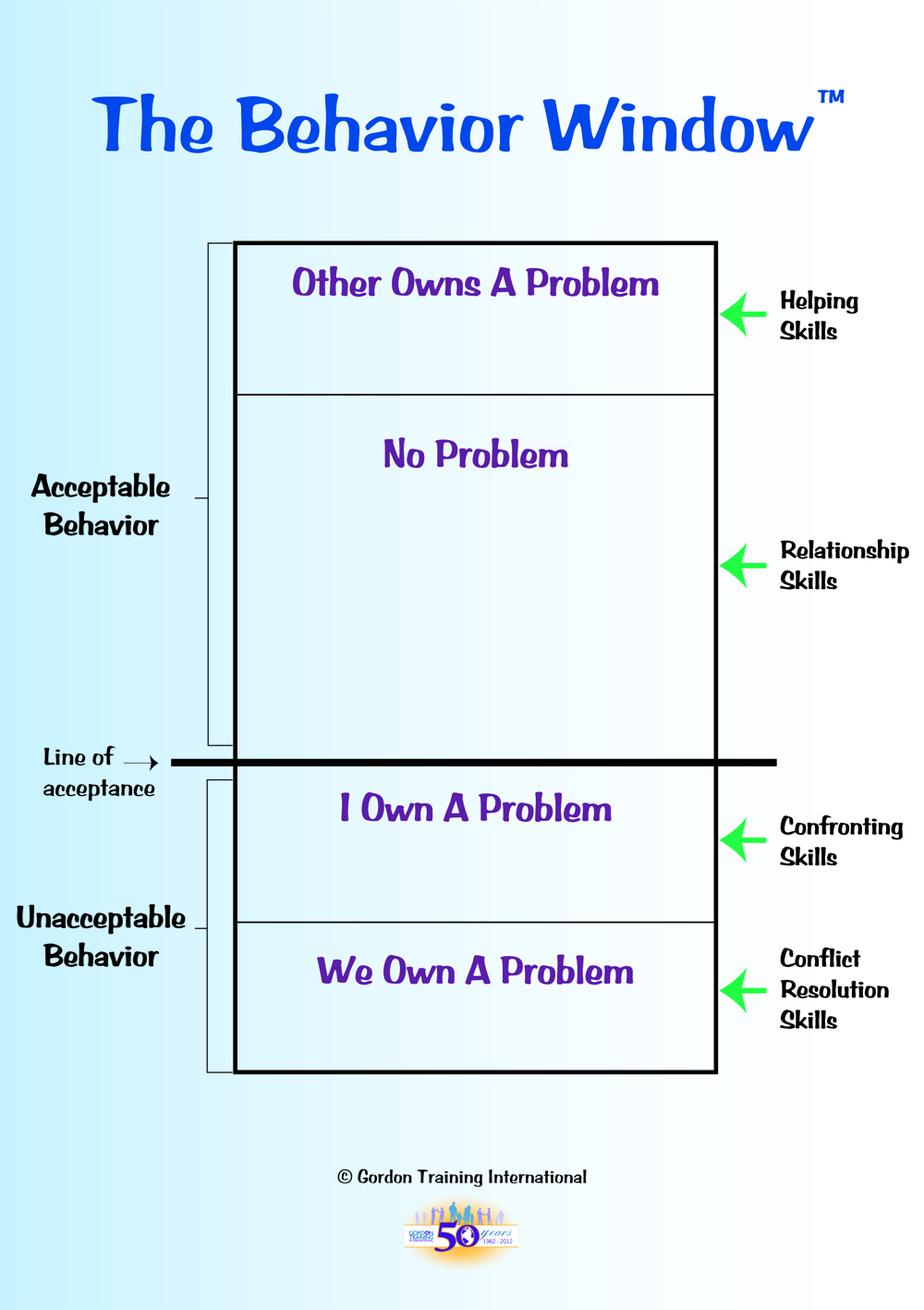

Behaviour Window (incorporating the concept of Problem Ownership): A simple but effective visual and conceptual model, that helps parents objectively observe a situation, and then determine the best skill (or combination of skills) to use with their children.

Behaviour Window (incorporating the concept of Problem Ownership): A simple but effective visual and conceptual model, that helps parents objectively observe a situation, and then determine the best skill (or combination of skills) to use with their children.

Children do not ‘misbehave’: The concept that children do not ‘misbehave’, but instead behave simply to meet a need, is a revelation to many parents. P.E.T. turns misbehaviour around to being a problem of competing needs – parent and child’s.

Modelling: Part of the suite of options in resolving values conflicts, modelling refers to parents ‘living what they believe’ – demonstrating their values through their behaviour and actions.

Differences in approaches to parenting

Basically, there are two approaches to parenting (Kohn, 2005; Porter, 2008). Perhaps the best known is the ‘behavioural’ model, where parents rely on rewards and punishment to obtain compliance from their children. The alternative approach, known as a relationship, or humanist, approach, does not use reward or punishment, but instead depends on the relationship to develop an inner discipline. Parent Effectiveness Training takes a relationship-based approach to parenting.

Table 1 summarises some of the differences between the two approaches.

| Table 1: Differences Between Parenting ApproachesDifferences between approaches: | |

| P.E.T. |

Behavioural |

| Child and parent centered | Parent centered |

| Communication skills | Behavioural management skills |

| Emphasis on listening to; understanding child | Emphasis on getting child to conform |

| Unconditional | Conditional (to be earned) |

| Enhances relationship over life | Targets behaviour in present time |

| General population | Initially developed for clinical intervention |

| Suitable for all ages – babes to adults | To age 12, then often different approach for teenagers |

| Does not use reward or punishment | Relies on reward and punishment |

| Parent as a partner, or guide | Parent in ‘supportive control’ |

| Solve problems within the relationship – win/win or no-lose | Aim for compliance from child – win/lose |

| Mutual respect | Conditional respect – when child ‘deserves’ it |

| Parents are people – can’t be consistent | Parents must be consistent |

| Looks behind the behaviour to the need | Reacts to the behaviour rather than the need |

| Does things ‘with’ children | Does things ‘to’ children |

| Democratic | Autocratic |

| Differences in outcomes between models: | |

| Emotional intelligence skills taught (child and parent) | Emotional intelligence not addressed |

| Resilience enhanced | Resilience skills not addressed |

| Internal, intrinsic motivation and ethical moral development | External behavioural motivation |

| Child acts out of consideration for others | Child acts out of consideration for self – “how will I be punished or rewarded for my behaviour?” |

| Life long relationship developed | Relationship improved, but not life long |

| Skills transferable across all relationships: partner, school friends, work relationships etc. | Skills specific for one age group; only for parents |

An article by Linda Adams (President of Gordon Training International) is a useful resource in terms of comparing parenting programs.

How P.E.T. Skills and Principles Achieve Evidence-based Outcomes

In this paper, I describe a selection of evidence-based attributes that lead to good life outcomes. These include: attachment (including attunement, reflective parental functioning and mentalizing); resilience; self-regulation and self-discipline; strong relationship with parents or carers; attribution of intent; and dealing with, or preventing, trauma. I then detail how P.E.T. helps parents and carers attain these qualities – for both their children, and themselves.

In this paper, I describe a selection of evidence-based attributes that lead to good life outcomes. These include: attachment (including attunement, reflective parental functioning and mentalizing); resilience; self-regulation and self-discipline; strong relationship with parents or carers; attribution of intent; and dealing with, or preventing, trauma. I then detail how P.E.T. helps parents and carers attain these qualities – for both their children, and themselves.

Attachment

What? ‘Attachment is a deep and enduring emotional bond that connects one person to another across time and space’ (McLeod, 2009) The term ‘attachment’ refers to a lasting tie with a caregiver (most often a parent). This relatively recent area of science in the child/parenting arena has been, and continues to be, extensively researched.

Specific areas that are essential in the formation of attachment are ‘attunement’, ‘reflective parental functioning’, and ‘mentalizing’ (or ‘mindsight’).

In a nut shell:

- ‘Attunement’ means that, as a parent, you look and listen for the needs of your child, then respond accordingly. Being attuned to the needs of your baby or child is essential in developing a secure attachment

- ‘Reflective functioning’ is the ability to think about (reflect) on a child’s emotional experience, separate from the parent’s emotional experience. That is, we recognise that children have a mind of their own, and that they think and feel differently to us (the parent) – because our children have their own unique needs.

- ‘Mentalizing’ (or ‘mindsight’, as coined by Dr. Dan Siegel) refers to the ability to observe our own mind, and the minds of our children. Mentalizing recognises that our mental states are separate from our behaviour. In effect, mentalizing is ‘thinking about feeling’ – both for ourselves, and for others.

Why is it important? Attachment style can predict life chances for a child. The best outcome for children is if there is a ‘secure’ attachment. Secure attachment has numerous positive effects for children, including: developing an ability to trust; positive sense of self-worth; problem solving skills; autonomy; strong relationships; and ability to control their emotions. Worryingly, a recent study(ii) indicated that 1 in 4 children have insecure attachments with their parents. Research(iii) indicates that children with insecure attachments have more difficulty with their behaviour, and in other aspects of their lives.

Our capacity as parents to reflect on our own and our child’s internal experience is ‘crucial to the development of secure attachment’ (Slade, A. 2005) .

Our capacity as parents to reflect on our own and our child’s internal experience is ‘crucial to the development of secure attachment’ (Slade, A. 2005) .

How does P.E.T. help? If implemented well, the P.E.T. skills and philosophy help develop a securely attached baby and child. In particular:

Active Listening helps a parent become ‘attuned’ to their child – from the moment their child is born. Active Listening helps you become attuned because it helps you understand what is happening for your child. The first step in Active Listening is to become aware of your baby’s cues and decipher their meaning in terms of your baby’s needs. Responding to your baby’s cues and then attending to their needs is being attuned.

Behaviour Window and Problem Ownership Models: These foundation aspects of P.E.T. help parents to develop reflective parental functioning, and mentalizing.

The Behaviour Window helps parents understand themselves, and understand others. Parents can use this visual model to get in touch with their triggers, their feelings, their beliefs and values. The Behaviour Window aids parents to ‘mentalize’.

Problem Ownership helps parents recognise that their children are separate from themselves, with children having their own unique needs and internal experience. It is this framework, I think, that is useful in aiding the process of ‘reflective parental functioning’.

Illustrations of reflective functioning and mentalizing:

Reflective functioning and mentalizing describe your ability to be in touch with your own internal state (experiences, values, feelings), and how that might affect your behaviour. For example, if you’ve had a good day at work and feel relaxed, you might be accepting of your child’s behaviour (such as singing in a loud voice). You might laugh, or even join in the singing. However, if you feel frustrated because you’re tired and had a bad day, you might be less accepting of your child singing loudly, and perhaps even yell at him or her.

The Behaviour Window will help you understand why you have responded to your child’s behaviour by either yelling or laughing (mentalizing). Problem Ownership will help you separate your feelings and responses from your child’s actions (reflective parental functioning).

The Behaviour Window will help you understand why you have responded to your child’s behaviour by either yelling or laughing (mentalizing). Problem Ownership will help you separate your feelings and responses from your child’s actions (reflective parental functioning).

Similarly, children have their own internal experience, which leads to their behaviour. Your 3-year-old son might be really frustrated because his blocks keep falling down, no matter how hard he tries. So he begins to kick and yell at them. If he can recognise that he is frustrated (because what he wants is at odds with his level of skill), then he can begin the process of self-regulation, and perhaps tell you he is frustrated, rather than kick at his blocks.

Resilience

What? Resilience is the ability to endure, or overcome, adversity. Even when there may have been risk factors in their childhood, resilient people have the capacity to be confident, empathic, and accomplished. From the useful resource on Being Resilient (by Kidshelpline), the skills children require to be resilient include: social skills; self-regulation; problem-solving skills and realistic expectations. Resilience is a continuing process – it is not ‘set’ within a person, but can be learned and enhanced.

Why is it important? If children are resilient, they are more likely to manage and overcome the difficulties that life places before them, and remain psychologically and emotionally healthy – even grow from their experiences.

How does P.E.T. help? One of the biggest factors in developing resilience is a strong parental relationship. Ensuring a child feels valued and accepted; that she or he is in a physically and psychologically safe environment; and has positive role-modelling from parents all contribute to the development of resilience.

The entire P.E.T skill set is aimed at developing and maintaining warm, close, respectful relationships. In particular, Active Listening and problem solving help develop the essential quality of resilience.

When a parent Active Listens to their child, they give their child a safe, connected space in which to experience an upset (to be sad, to be worried, to be frustrated). Children discover that they have the ability to solve their own problems. They learn they can work through and survive adversity. This is the basis of resilience.

Let’s look at four-year-old Karen, who does not want to go to childcare. Dad listens to her.

“You’re really sad about going to childcare, and you’re annoyed you don’t have a choice. It also sounds like you’re worried about missing Mummy and me and the dog. You’d prefer to stay home.”

Dad has listened to, and acknowledged, Karen’s sadness. Then when he sees, and hears, that he has heard her accurately, he asks if they can discuss some ideas about how to solve the issue (problem solving).

“What would help you to be OK to go to childcare?”

Karen thinks, then says,

“I’ll take this toy – it has Mummy’s perfume on it, so I can smell it and feel better”.

Throughout her childhood, Karen will experience upsets like this. The issues will inevitably increase in difficulty, such as friendship losses, or loss of grandparents. Karen learns, through the support of her family and their use of relationship skills such as Active Listening, that she has the ability to get through life’s troubles. She is able to problem-solve, and she will also feel confident to reach out for help if the situation is too big to handle by herself. She will value and trust herself, and have a good sense of self-worth. These are all significant factors in the development of resilience.

Self-Regulation and Self-Discipline

What? Self-regulation is the ability to manage your behaviour and your emotions. So, when you are upset you might find a way to calm yourself. Regulating yourself is related to reflective functioning – it requires some thinking about what you are feeling. That is, some awareness of what is happening within you. Once you have noticed your feelings (and their possible cause), you can then make some decisions about how you might behave. Self-regulation is important for both children and adults. Dr. Gordon’s book, Teaching Children Self-Discipline (1989) explores this topic in detail.

Why is it important? Self-regulation is related to a child’s ability to do well in childhood and adult life. Children who have good self-regulation are able to concentrate, take turns, develop autonomy, and develop strong relationships.

How does P.E.T. help?

Parents and self-regulation:

Behaviour Window; Problem Ownership and Active Listening:

When parents understand themselves and their feelings (Behaviour Window); and when they are able to empathise with their child (Problem Ownership and Active Listening), they are more likely to manage their own behaviour (for example, yell less).

I-Messages:

I-Messages are essential in learning the skill of self-regulation. The skill help parents express their feelings in a way that is safe, non-blameful, and maintains the relationship.

Using an I-Message means we have to think about how we feel, and how we are affected by, our child’s behaviour. We then communicate this to our child using careful, respectful language. This means we are regulating our behaviour. We are choosing to talk about how we feel, rather than showing how we feel (such as yelling or smacking). We are managing our emotions and our behaviour.

Another outcome of an I-Message is that often, when a parent looks for a cost to themselves of their child’s behaviour, they discover there is none. As a parent, you may then change your perception of your child’s behaviour, and be less likely to react negatively (so, are more likely to be self-regulated).

Let’s say I walk into my daughter’s room. There are toys scattered all over the floor. I can’t bear the ‘mess’ and ask her to clean it up. What is the cost to me of her toys on the floor in her room? To her, the room is not a ‘mess’ – she has carefully placed all toys in their friendship positions. I don’t need the room clean this instant. I begin to question myself. Really, if I have a pathway to her bed, is it essential that all toys be off the floor? After thinking this through, I decide to say nothing – and she invites me to play. I have shown self-discipline, and as I play with my child, I reflect on the warmth of our relationship.

Let’s say I walk into my daughter’s room. There are toys scattered all over the floor. I can’t bear the ‘mess’ and ask her to clean it up. What is the cost to me of her toys on the floor in her room? To her, the room is not a ‘mess’ – she has carefully placed all toys in their friendship positions. I don’t need the room clean this instant. I begin to question myself. Really, if I have a pathway to her bed, is it essential that all toys be off the floor? After thinking this through, I decide to say nothing – and she invites me to play. I have shown self-discipline, and as I play with my child, I reflect on the warmth of our relationship.

Helping children develop self-regulation:

Active Listening coaches children about their emotions. Children begin to identify their own feelings. They begin to translate what they feel in their bodies to named emotions. Children discover they can calm themselves (self-regulate), as they move from emotion to cognition.

Modelling of good self-regulation by the parent will be invaluable in helping children develop this characteristic.

Not using rewards and punishment is important in assisting children to develop self-discipline. The skills and principles of P.E.T., particularly no-lose conflict resolution, help parents find an alternative to using rewards and punishment.

Rewards and punishment are external means of controlling a child’s behaviour. Children stop their behaviour because of fear of punishment (by their parent or teacher), or because they want a reward (from their parent or teacher). When parents don’t use reward and punishment, but instead rely on the relationship, children develop an ‘internal locus of control’ – an inner discipline. Children with self-discipline have the capacity to change their behaviour through applying their own knowledge of themselves, and what is acceptable behaviour in their community.

Social and Emotional Intelligence (SEI); and Empathy

What? Emotional intelligence (EI) is the ability to ‘perceive, control and evaluate emotions’(vi) in both ourselves, and other people. Daniel Goleman helped bring EI to prominence in his book Emotional Intelligence (1997). Social intelligence is the ability to get on with other people. Empathy is generally described as the ability to recognise and understand other people’s emotions, combined with the capacity to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling. Emotional intelligence is at the root of empathy.

Why is it important? The importance of social and emotional intelligence has been studied over decades, and is championed by the Nobel laureate, Dr. James Heckman. Children need SEI to develop to their full potential and lead productive lives. SEI may be more important than IQ (intelligence quotient)(vii) in determining positive outcomes for children. Children who are empathic are more likely to achieve personal, relationship and career success.

How does P.E.T. help? All the P.E.T. skills help children develop SEI and empathy.

Active Listening is a major skill that helps our children acquire these characteristics. When we listen actively to our children, we are helping them recognise and name the emotions they are experiencing. In effect, we are ‘emotion coaching’. This helps our children understand and be aware of their own emotions. We are also modelling empathy when we Active Listen.

Modelling through I-Messages is invaluable in developing emotional intelligence and empathy. I-Messages generally contain a feeling word to help describe a parent’s current emotion. In this way, children learn about other people’s feelings. They see feelings expressed in context with whatever may be happening for the parent (modelling). A carefully worded I-Message comes across as an appeal for help. Children understand what is happening for their parent, and how their parent feels (empathic concern(viii)). Parents who model empathy for others – expressing their concern about how another person feels – are helping their children develop empathy.

Strong Relationship with parents or caregivers

There is good evidence on the importance of relationship between parents and their children, and the outcome for children. A warm and connected relationship can help insulate a child from negative life outcomes, and promote compassionate autonomy.

In their Report Card: The wellbeing of young Australians (2013 p8)(ix), ARACY (Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth) spoke of the importance of children and young people being ‘loved and safe’. ‘Loved and safe’ was an outcome of positive family relationships, and resulted in confident, resilient children with good self esteem, who formed secure attachments and had ‘pro-social peer connections’.

According to Robinson et al (2010)(x) , ‘the emotional and psychological support offered via a warm and communicative child-parent relationship’ is important in early childhood, but even more so in adolescence. Parents often underestimate how important they are in the life of their teenager and young adult. This review elevates the importance of a positive relationship between parents and their young person.

Five elements of a relationship that would lead to secure attachment were outlined by Schofield and Beek, 2009 (cited by Robinson et al, 2010). The essential relationship components were:

• availability – helping young people to trust;

• sensitivity – helping young people to manage feelings and behaviours;

• acceptance – building the self-esteem of the young person;

• co-operation – helping young people to feel effective; and

• family membership – helping young people belong.

How does P.E.T. help? The entire suite of P.E.T. skills and principles help form, enhance, and maintain a positive relationship with children and young people. The communication skills are respectful, accepting, assertive, non-blameful, and promote warmth. P.E.T. helps children change their behaviour because they want to cooperate within a family unit.

The practical relationship skills taught to parents and caregivers in P.E.T. helps deliver favourable life outcomes for children.

Attribution of intent

What? When we ‘attribute intent’, we make assumptions about the reasons for our children’s behaviour.

Why is it important? At its worst, a parent’s belief that there is ‘hostile’ intent to their child’s behaviour, can lead to child abuse(xi). In general, making assumptions (generally negative) about the intentions behind behaviour can lead to us blaming our children, and have a damaging effect on our relationship with them. ‘Attributing intent’ means we stop looking at any needs the child might have (that are being expressed in their behaviour). Instead, we focus on their behaviour, and our assumptions regarding the reasons for their behaviour.

How does P.E.T. help? P.E.T. helps parents identify behaviour (something we can see, hear, feel, taste, smell). Through Active Listening, parents are encouraged to respond to their child’s feelings and needs (shown by their behaviour). Empathic listening can uncover the need that lies behind their child’s behaviour. This takes us full circle, back to Dr. Gordon’s original guiding principle: that children behave simply to meet a need.

Trauma.

What? Trauma is ‘a state of high arousal in which normal coping mechanisms are overwhelmed in response to perceptions of threat’ (Cozolino, 2002 p.270 (xii), cited by Adult Survivors of Child Abuse training materials).

In other words, trauma occurs when a person is overwhelmed by a situation, and they have no inner resources with which to cope. There may be a feeling of immense powerlessness.

Why is it important? Children’s brains can be shaped by trauma. If trauma is not resolved, it can have a negative effect on a wide range of abilities in later life. Children who are traumatised have problems with controlling their emotions, with relationships, and with reasoning when they are feeling stressed. Adults who have suffered trauma can suffer emotional and physical symptoms. 90% of mental health patients, and 75% of people with substance abuse, report trauma and abuse histories (personal communication: Adults Surviving Child Abuse training (ACSA, 2014). Fortunately, it is possible to recover from trauma.

How does P.E.T. help? According to ACSA, research shows that children can be helped to overcome trauma in relationship. In their chapter on buffering trauma(xiii), Ludy-Dobson and Perry state ‘These powerful regulating effects of healthy relational interactions on the individual [social–emotional cues of acceptance, understanding, compassion, and empathy] . . . are at the core of relationally based protective mechanisms that help us survive and thrive following trauma and loss.’(emphasis inserted)

P.E.T. helps parents develop healthy relationships with children, and it is within healthy relationships that children can overcome (or avoid) trauma.

Parents may endure unresolved trauma from their childhood, which can then affect the way they parent their own children. Parents that have not experienced a positive relationship with their own parents, can in turn raise traumatised children (for example, being unable to connect emotionally). P.E.T. has a step-by-step, easy to learn, practical process, where parents can learn the skills of connection and relationship. I believe P.E.T. may help break the generational trauma cycle.

Importantly, P.E.T. avoids the use of reward and punishment.

Consider the outcome of punishing a traumatised child with ‘time-out’. Time-out is where children are to remain by themselves (in another room, or separate from others in the same room) for a time determined by the parent, teacher or carer. Essentially, time out isolates children from relationship. Neuroscience now shows that social isolation travels the same neural pathway as physical pain or illness. Children, particularly those that have suffered trauma, need connection and relationship – not isolation.

Conclusion

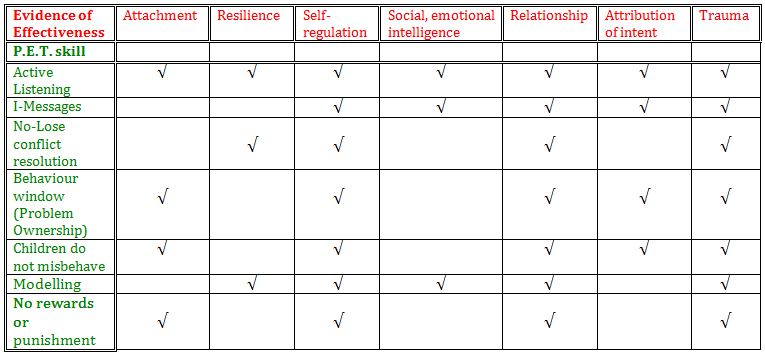

This article examined how individual aspects of the Parent Effectiveness Training program dovetailed with the current evidence on positive outcomes for children and parents. Table 2 breaks P.E.T. into its component parts, and indicates their applicability in achieving particular evidence-based life chances.

This article examined how individual aspects of the Parent Effectiveness Training program dovetailed with the current evidence on positive outcomes for children and parents. Table 2 breaks P.E.T. into its component parts, and indicates their applicability in achieving particular evidence-based life chances.

There is now strong evidence to validate the parenting skills and approach taught in Parent Effectiveness Training.

Today’s evidence is a testament to the vision and understanding of Dr. Gordon in 1962.

Table 2. Summary of Skills and Principles of P.E.T. and evidence-based attributes.

________________________________

i Wood, C, 2003. Helping Families Cope. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Family Matters, 65, 28-33.

ii McLeod, S. A. (2009). Attachment Theory. Retrieved from http://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.html

iii Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. (2014, March 27). Four in 10 infants lack strong parental attachments. ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 30, 2015 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/03/140327123540.htm

iv Benoit, D. (2004). Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatrics & Child Health, 9(8), 541–545. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2724160/

v Slade, A, 2005. Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, Volume 7, Issue 3, 269-281. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16210239. [Accessed 30 March 2015].

vi What is emotional intelligence? Definition, history and measures of emotional history. [ONLINE] Available at: http://psychology.about.com/od/personalitydevelopment/a/emotionalintell.htm [Accessed 30 March 2015].

vii IQ or EQ – Which One is More Important?[ONLINE] Available at: http://psychology.about.com/od/intelligence/fl/IQ-or-EQ-Which-One-Is-More-Important.htm [Accessed 30 March 2015].

viii “Empathy” — Who’s Got It, Who Does Not | Daniel Goleman. 2015. “Empathy” — Who’s Got It, Who Does Not | Daniel Goleman. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dan-goleman/empathy—whos-got-it-who_b_195178.html. [Accessed 30 March 2015].

ix Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, (2013), Report Card: the wellbeing of young Australians. [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.aracy.org.au/documents/item/104 [Accessed 25 April 15].

x Robinson, E, Power, L, and Allan, D. March, 2010. What works with adolescents? Family connections and involvement in interventions for adolescent problem behaviours. Australian Institute of Family Studies. AFRC Briefing Paper No 16. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www3.aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/what-works-adolescents-family-connections-and-involvem

xi Commonwealth Department of Families and Community Services, 2004. Parenting Information Project. Volume 1. P7

xii Cozolino, L., 2002. The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc. (cited in ASCA training material)

xiii Christine Ludy-Dobson and Dr Bruce Perry . 2010. https://childtrauma.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/The_Role_of_Healthy_Relational_Interactions_Perry.pdf. [ONLINE] Available at: http://childtrauma.org/. [Accessed 26 April 15].

Bibliography:

Gordon, T, 2000. Parent Effectiveness Training: The Proven Program for Raising Responsible Children. 3rd ed. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Gordon, T, 1989. Teaching Children Self Discipline: At Home and at School. 1st ed. America: Random House.

Kohn, A., 2005. Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishment to Love and Reason. 1st ed. New York: ATRIA Books.

Porter, L., 2008. Children are People Too. 4th ed. Adelaide: East Street Publications.

© Larissa Dann. 2015. All rights reserved