People are conditioned almost from infancy to think of feelings as bad and dangerous—enemies of good human relationships. People grow up afraid of feelings—their own and those of others around them…Leaders should treat feelings as “friendly,” not dangerous. Feelings should be welcomed because they are cues and clues that some problem exists. With this attitude, leaders will not ignore the signals or, worse yet, roadblock the senders of such messages. Instead they should encourage people through Active Listening to go beyond their feelings to get to the underlying problem. –Dr. Thomas Gordon, Leader Effectiveness Training, pp. 81-83

“The other day when the boss talked over me six times in the same meeting? He made me so mad.”

“That new thing with having to track our time by the tenth of an hour is stressing me out. I want to punch whoever came up with that idiotic idea.”

“I hate what’s going on around here since we outsourced the call center. It’s driving me crazy that I can’t understand a word people are saying on these support calls.”

Dr. Gordon was right; he held up a psychological mirror and showed us the truth about how most of us are conditioned not to give voice to negative emotions. And furthermore, if we hear others speaking negatively about their own emotions, chances are good that our first instinct will be to use one of the roadblocks to “help” them get over, around, or beyond the feeling.

If we’re not born-and-bred gossips, trained therapists, or naturally gifted at helping others work through their problems using the Socratic method, most of us tend to default to fight-or-flight when we’re faced with others’ negative feelings. And unless we absolutely have to fight, most of us flee.

We gladly join in conversations about feelings that are positive—attagirls, celebrations, congratulations, love-fests. We know how to handle those. Our parents, teachers and coaches modeled such conversations for us as we grew up.

But when somebody breaks one of our biggest unspoken taboos—if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all—well, that’s when things get sticky. Few people ever receive structured, evidence-based training, coaching, or mentoring in how to respond constructively when others express negative emotions—like anger, depression, sadness, stress, and the like.

And yet in organizations, negative emotions can contain critical insights and data. Sometimes that information is just as real, valid, and valuable to the organization’s decision-making as massive spreadsheets from the CRM system. Your people can tell you a lot about what’s going on below the surface—if you’re listening.

Nothing to Fear Here

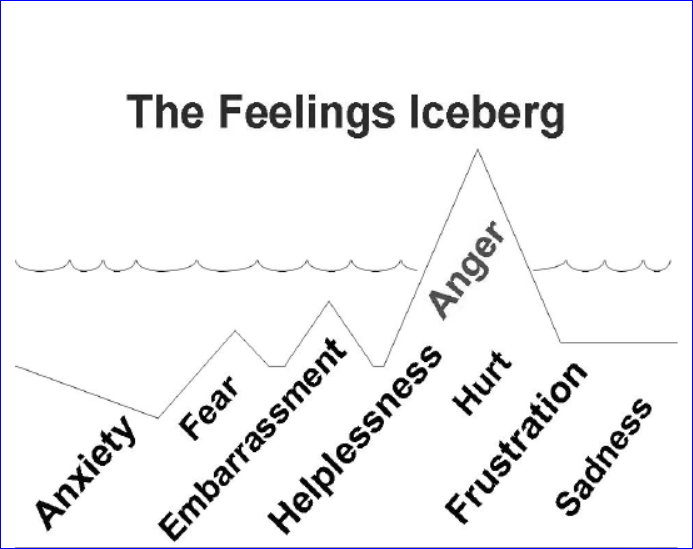

The Feelings Iceberg is a model that has been widely used and adapted through the years across many psychological traditions, from Freud to humanist Virgina Satir to every program offered by Gordon Training International, to help people understand a simple concept: Anger isn’t the beginning and end of negative emotions.

Anger, in fact, is usually a secondary emotion. That means some other emotion below the surface is the actual source of the problem causing somebody distress; it is simply being expressed as anger. (In the workplace, these expressions may be further muted because genuine anger is frowned upon in most workplaces, so the most people may be willing to say is “frustrated” or “upset” or even the euphemistic “extremely disappointed.”)

Still, when people say they are “angry” (or frustrated/upset/extremely disappointed), the primary emotion is generally an emotion other than anger—something even deeper, and something more troubling to the person’s basic ability to get his or her needs met.

Take being talked over in a meeting (repeatedly) by the boss. Would it be reasonable to feel angry afterwards? Sure! But why? What emotions might lie under the anger? Well, somebody in that situation might, if pressed, say “I was embarrassed in the meeting every time it happened. And I felt humiliated in front of my peers. I think my boss doesn’t respect me. I also wonder that lack of respect means she doesn’t think I’m good at my job. I feel threatened. I worry my job may be in jeopardy.”

All of these feelings are intensely vulnerable feelings—feelings that, frankly, are much harder to express than saying, with a big, puffed-up chest, “I AM ANGRY! YOU CANNOT PUSH ME AROUND!” Anger is a mask that attempts to hide vulnerability.

Emotions, like ice cream, comes in an unimaginable number of flavors. “Anger” is vanilla. Learning to speak about our deeper, primary emotions as we learn to speak about problems should be no more threatening than learning to speak about pecan-praline, or fudge brownie swirl, or strawberry ripple.

The job of a skilled Active Listener is to sit with a person who has expressed a secondary emotion (anger) and chip away that top layer of the iceberg and get at what lies below the surface.

Leader Effectiveness Training gives leaders the tools they need to help others find the language to accurately describe vulnerable, uncomfortable feelings. It’s a skill, like most things in life, and without exposure, support, practice, and reinforcement, talking about feelings simply isn’t something many of us are going to get better at.